When Behavior Is Communication: Rethinking Challenging Situations in Dementia Care

Challenging situations are a reality of dementia care—but how you interpret them shapes everything that follows. This article invites you to reframe behavior as communication and approach difficult moments with greater clarity, empathy, and clinical intention.

January 21, 2026

7 min. read

Over the years, I’ve heard just about every label you can imagine for people living with dementia: resistant, combative, difficult, uncooperative. And every time I hear those words, I pause. Not because I don’t understand where they come from—I do. I’ve been in those moments too, when safety feels uncertain, time is short, and emotions are running high.

But I’ve also learned something along the way: the words we use quietly shape the care we give.

When we call something a problem behavior, it changes our posture. We stop listening and start managing. We stop wondering and start reacting. And in doing that, we often miss the most important truth of all: many of the so-called behaviors we struggle with in dementia care are not problems to be fixed. They are messages waiting to be understood.

Why this shift matters clinically

In healthcare, language doesn’t just describe reality—it creates it. If we walk into a room thinking a patient is aggressive, our body tenses before we ever say a word. If we believe someone is resistant, we push harder to get compliance. But when we see distress instead of defiance, everything changes. Our voice softens, our pace slows. We start paying attention to what might be wrong rather than what needs to be controlled.

People living with dementia are navigating a world that no longer makes sense the way it once did. They may not be able to explain what hurts, what frightens them, or what feels overwhelming. That doesn’t mean they’ve stopped communicating; it means their communication has changed.

Once we begin to see behavior as communication, we stop asking, How do I make this stop? and start asking, What is this person trying to tell me? That single shift doesn’t just improve care—it changes how it feels to do the work.

Behavior as an expression of unmet need

Most of the challenging moments I’ve witnessed in dementia care make a lot more sense once you look beneath the surface.

Often, what we label as noncompliance is really confusion about what’s happening in the moment. What looks like aggression can be fear showing up in the only way it can. And when someone wanders, it’s rarely about being disruptive—it’s more often about searching for something familiar, something meaningful, something that once made sense to them.

When cognitive abilities change, the world can start to feel unpredictable and unsafe. Imagine being asked to do things you don’t fully understand, in places that no longer feel familiar, by people whose intentions you can’t always interpret. If that were your reality, you would likely push back, too.

So instead of asking, How do I make this stop? I invite you to ask, What might be underneath this?

Is this distress?

Is this confusion?

Is this pain, fear, or loss of control showing up as they are able to communicate?

Curiosity has the power to transform a difficult encounter into a meaningful moment of connection.

Remembering the person behind the diagnosis

One of the hardest habits to break in dementia care is letting the diagnosis speak louder than the person.

Every individual living with dementia had a life long before memory and reasoning changed. They worked, they raised families, they built routines and identities that mattered to them. Those parts don’t disappear when skills fade. In many ways, they become even more important.

I’ve seen it time and time again: a woman who spent her life caring for children finds deep purpose in nurturing a baby doll. A man who worked with his hands all his life grows restless when he no longer has work to do. Once you understand who someone has been, their behavior today starts to make sense in a different way.

This is where care stops being about tasks and starts being about relationships. When we take the time to learn a person’s story, we don’t just reduce distress—we restore dignity. And dignity has a way of changing everything about an interaction.

Why every moment is more complex than it looks

Challenging situations in dementia care rarely have a single cause. Most of the time, what we see on the surface is the result of several things coming together at once.

Sometimes the story starts with the person—their history, their personality, the abilities they’ve lost, and the ones that remain. Other times it’s the environment that tips the balance: too much noise, too little stimulation, spaces that overwhelm or confuse. And more often than we like to admit, it’s us—our tone, our timing, our own stress level that day.

When we look at only one piece of that picture, it’s easy to feel stuck. But when we step back and consider the whole situation, we often realize that what seemed like a problem behavior is really a mismatch between what the person needs and what the moment is offering.

That’s where real clinical reasoning lives, not in fixing people, but in shaping interactions so that people living with dementia have a better chance to succeed.

A word about you, the clinician

I want to pause here and talk directly to you.

This work is hard. Not just physically, but emotionally. When you care deeply and still feel like you’re falling short, that weighs on you. When you replay a difficult interaction in your mind on the drive home, wondering what you could have done differently, that weighs on you. When you feel like you’re always reacting rather than truly helping, that weighs on you, too.

If you feel exhausted sometimes, that doesn’t mean you’re failing. It means you care.

We talk a lot about caring for people living with dementia—and rightly so. But we don’t always talk enough about caring for the people who care for them. You are part of every interaction. Your well-being, your patience, and your support system matter more than you may realize.

When we begin to see challenging moments not as personal failures but as opportunities to learn, adjust, and try again, something shifts inside us, too. The work stays hard—but it also becomes more meaningful.

Where this perspective leads

Seeing behavior as communication is a powerful starting point. But understanding the idea is only the beginning.

What most clinicians really want to know is what to do in the moment:

How to stay grounded when things escalate.

How to change their approach without losing control of the situation.

How to support someone who is scared or angry when they themselves feel overwhelmed.

Those questions don’t come with simple answers. They take practice, reflection, guidance, and support.

In my course series, Accepting the Challenge, we spend time turning this mindset into real-world clinical practice—looking at how to approach challenging situations with intention instead of instinct, and how to build habits that truly change the experience for everyone involved. This article is meant to open the door to that way of thinking, but the course is where we walk through it together.

When we change the lens, we change the moment

Every person living with dementia is doing the best they can with the brain they have today. And every clinician working with them is doing the best they can with the time, energy, and resources they have in that moment.

When we choose to see behavior as communication instead of confrontation, something remarkable happens. Challenging situations become opportunities not just to provide support, but to deepen connection, restore dignity, and grow in our own clinical practice.

If this perspective resonates with you, I hope you’ll continue the journey with me through the Accepting the Challenge series:

Accepting the Challenge: Positive Physical Approach™ for Dementia

Accepting the Challenge: Challenging Situations in Dementia Care

Not because there’s one right way to do this work—but because the more we learn, the more thoughtfully we can show up for the people who depend on us.

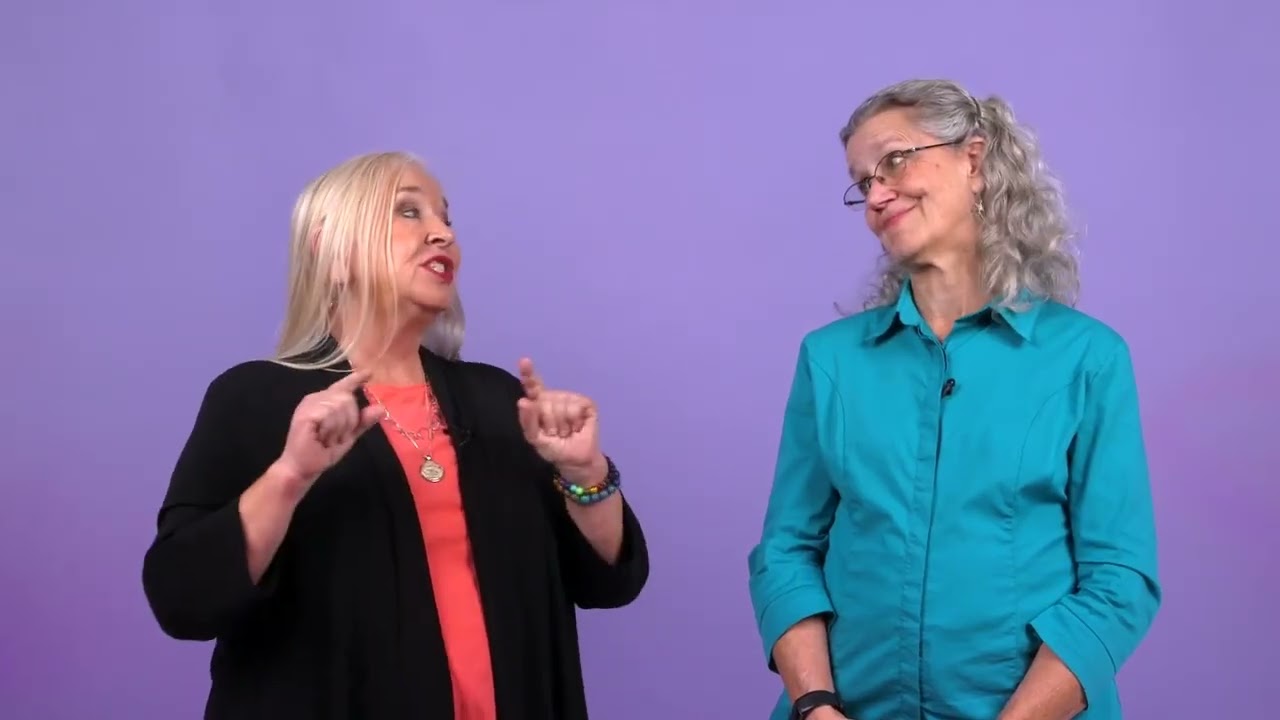

Below, watch Teepa Snow and Melanie Bunn discuss meaningful days in dementia care in this brief clip from their Medbridge course "Accepting the Challenge: Challenging Situations in Dementia Care."