Ottawa Ankle Rules: When to Order an Ankle X-Ray

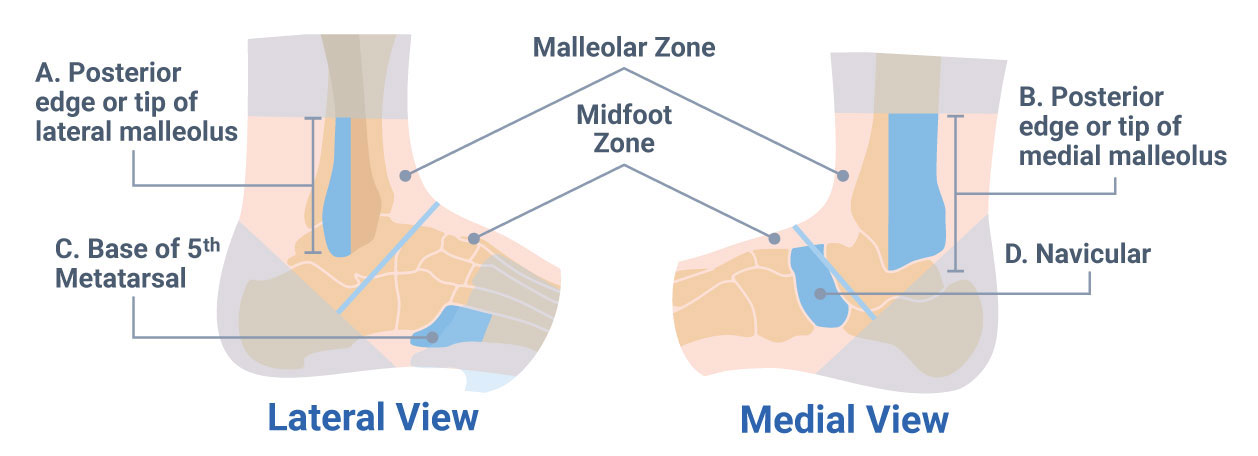

Knowing when to order X-rays, or even what to order, can be confusing. The Ottawa Ankle Rules, developed by Stiell, specifies the criteria to be met before ordering X-rays for a patient presenting with an acute ankle injury.10,11,13,14 The instructions and associated figure below layout these guidelines.

What Are the Ottawa Ankle Rules?

Using the diagram below we can determine when an ankle x-ray series is required. The rule’s reported sensitivity is 1.0, so x-rays are necessary if any of the below are met:

A. There is any pain in the malleolar zone and any of the following:

- Bone tenderness at A

- Bone tenderness at B

- Inability to take 4 steps both immediately and in the emergency department

B. There is any pain in the midfoot zone and any of the following:

- Bone tenderness at C

- Bone tenderness at D

- Inability to take 4 steps both immediately and in the emergency department

If neither of these criteria is present, no imaging is needed.

Sensitivity of the Ottawa Ankle Rules

The ottawa ankle rules have a 100% sensitivity for positive indication of malleolar fracture or mid-foot fracture, with a range of 82-100% for malleolar and 95-100% for midfoot.1 The negative likelihood for both regions were .08 and .07 in children, which then applied to the 15% fracture prevalence resulted in a less than 1.4% probability of a fracture following a negative test.1

Which Imaging Views to Order?

For a positive ankle fracture test, order the anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and internal oblique, or mortise, views. The mortise view allows for a better view of the ankle mortise and avoids the overlap that’s present on the AP view.

For a foot view, a foot-specific x-ray series needs to be ordered. A typical foot series would include the anteroposterior (AP), lateral and oblique views. The oblique view opens up the tarsals so you can better see down the planes of the foot.

Classifications for Ankle Fracture

Danis-Weber Classification System

Weber A – A fracture below the ankle mortis.

Weber B – A fracture at the level of the joint, with the tibiofibular ligaments usually intact.

Weber C – A fracture above the joint level with tears to the syndesmotic ligaments as well.

Lauge-Hansen Classification System

This classification scheme uses two-word descriptors to describe the mechanical mechanism of the injury. The first word describes the position of the foot at the time of injury and the second word describes the motion of the talus with respect to the leg. It’s either a supination/adduction for the foot position or pronation/abduction for the talus motion. The different combinations of the motions are broken out into different injuries:

Supination-Adduction

Stage 1: Transverse fracture of the lateral malleolus, at or below the level of anterior talo-fibular ligament, or a tear of lateral collateral ligament structures with the anterior talofibular ligament disrupted most often and frequently the calcaneofibular ligament also being torn.

Stage 2: Oblique fracture of medial malleolus.

Supination-External Rotation (SER)

This is the more common combination, occurring in 40-70% of ankle fractures. These can also be divided into stages based on severity:

Stage 1: Rupture of anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament

Stage 2: Oblique fracture or spiral fracture of the lateral malleolus

Stage 3: Rupture of post tibiofibular ligament or fracture of posterior malleolus of tibia

Stage 4: Transverse (sometimes oblique) fracture of medial malleolus

Pronation-Abduction

This fracture occurs in less than 5% of ankle fractures.

Stage 1: Rupture of the deltoid ligament or transverse fracture of the medial malleolus

Stage 2: Rupture of the anterior and posterior inferior tibiotalofibular ligaments or bony avulsion

Stage 3: Oblique fracture of the fibula at the level of the syndesmosis

Pronation-External Rotation (PER)

Stage 1: Rupture of the deltoid ligament or transverse fracture of the medial malleolus

Stage 2: Rupture of the anterior inferior tibiotalofibular ligaments or bony avulsion

Stage 3: Spiral/Oblique fracture of the fibula above the level of the syndesmosis

Stage 4: Rupture of the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament or fracture of the posterior malleolus

Pronation-Dorsiflexion

Stage 1: Fracture of the medial malleolus

Stage 2: Fracture of the anterior lip of the tibia

Stage 3: Fracture of the supramalleolar aspect of the fibula

Stage 4: Rupture of the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament or fracture of the posterior malleolus

Common Fractures of the Ankle

Common fractures of the ankle include the Maisonneuve, Tillaux, Lisfranc, and Jones fractures.

Maisonneuve Fracture

The Maisonneuve is usually a result of an external rotation force to the ankle with transmission of that force through the interosseous membrane, exiting through the proximal fibula. The length of the fibula should be palpated with these patients as there is often another fracture at the proximal end, usually around the head and neck of the fibula.

Tillaux Fracture

The Tillaux fracture is a fracture of immature bone. Plain x-ray is the imaging recommendation. To see better bone definition, a CT or MRI is the next step.

Lisfranc Fracture

A Lisfranc fracture is a mid-foot fracture, and considered with any fracture of the tarsals or metatarsal joints. Lisfranc fractures are often missed in the ER and finding them can be difficult. Making sure all the anatomic structures line up is one way to discover Lisfranc injuries. Medial plantar bruising is also a hallmark sign of a Lisfranc fracture. An MRI can also assist in diagnoses with these easy to miss injuries.

Jones Fracture

The Jones fracture is a secondary fracture of the base of the fifth metatarsal. An AP or oblique x-ray should provide the best imaging views to identify Jones fractures.

Why use the Ottawa Ankle Rules?

By knowing these rules and using them correctly, you can:

- Appropriately treat and refer patients

- Keep costs of health care down

- Decrease needless imaging

- Decrease harm to the patient by excess radiation exposure

- Prevent unnecessary interventions

This is just one example of how clinical criteria can help you with your decision to order imaging. Whether it’s the Ottawa Ankle Rules or another clinical decision directive, if you use and understand these rules, you can easily improve your patient outcomes.

- Bachmann LM, Haberzeth S, Steurer J, ter Riet G. The accuracy of the Ottawa knee rule to rule out knee fractures: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. Jan 20 2004;140(2):121-124.

- Brand DA, Frazier WH, Kohlhepp WC, et al. A protocol for selecting patients with injured extremities who need x-rays. N Engl J Med. Feb 11 1982;306(6):333-339.

- Docherty MA, Schwab RA, Ma OJ. Can elbow extension be used as a test of clinically significant injury? South Med J. May 2002;95(5):539-541.

- Hall FM. The Canadian C-spine rule. N Engl J Med. Apr 1 2004;350(14):1467-1469; author reply 1467-1469.

- Hawley C, Rosenblatt R. Ottawa and Pittsburgh rules for acute knee injuries. J Fam Pract. Oct 1998;47(4):254-255.

- Mower WR, Hoffman J. Comparison of the Canadian C-Spine rule and NEXUS decision instrument in evaluating blunt trauma patients for cervical spine injury. Ann Emerg Med. Apr 2004;43(4):515-517.

- Parvizi J, Wayman J, Kelly P, Moran CG. Combining the clinical signs improves diagnosis of scaphoid fractures. A prospective study with follow-up. J Hand Surg Br. Jun 1998;23(3):324-327.

- Phillips TG, Reibach AM, Slomiany WP. Diagnosis and management of scaphoid fractures. Am Fam Physician. Sep 1 2004;70(5):879-884.

- Springer BA, Arciero RA, Tenuta JJ, Taylor DC. A prospective study of modified Ottawa ankle rules in a military population. Interobserver agreement between physical therapists and orthopaedic surgeons. Am J Sports Med. Nov-Dec 2000;28(6):864-868.

- Stiell I. Ottawa ankle rules. Can Fam Physician. Mar 1996;42:478-480.

- Stiell I, Wells G, Laupacis A, et al. Multicentre trial to introduce the Ottawa ankle rules for use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Multicentre Ankle Rule Study Group. Bmj. Sep 2 1995;311(7005):594-597.

- Stiell IG, Clement CM, McKnight RD, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. Dec 25 2003;349(26):2510-2518.

- Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, et al. Decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Refinement and prospective validation. Jama. Mar 3 1993;269(9):1127-1132.

- Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, Wells GA. Ottawa ankle rules for radiography of acute injuries. N Z Med J. Mar 22 1995;108(996):111.

- Stiell IG, Lesiuk H, Wells GA, et al. The Canadian CT Head Rule Study for patients with minor head injury: rationale, objectives, and methodology for phase I (derivation). Ann Emerg Med. Aug 2001;38(2):160-169.

- Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. Jama. Oct 17 2001;286(15):1841-1848.

- Tandeter HB, Shvartzman P. Acute knee injuries: use of decision rules for selective radiograph ordering. Am Fam Physician. Dec 1999;60(9):2599-2608.

- Wasson JH, Sox HC. Clinical prediction rules. Have they come of age? Jama. Feb 28 1996;275(8):641-642.